The complementary technologies of network functions virtualisation (NFV) and software-defined networks (SDN) have made slower progress than was hoped.

Now we’re looking to implement zero-touch operations, automation and artificial intelligence (AI) in the 5G era.

Slow progress is due to many factors, but one aspect in particular that is deeply troubling is the continuing tension and distrust between operators and the established equipment providers. Klaus Martiny, Senior Programme Manager with Deutsche Telekom, has been involved in standardising NFV from the outset. He is currently leading ETSI’s industry standardisation group for Zero-touch Network and Service Management (ZSM).

Speaking at FutureNet World in London, he said there is “a gap in the belief that [NFV] is the best technology since [it began in] 2012 or 2013 until now; it is something of a ping-pong between suppliers and operators. The operators say the vendors are not doing what [we’re] interested in and the vendors say the operators are not ordering what we are offering. It’s an on-going tradition.”

Slow but steady progress

Despite this, some operators are making progress. Walter Miron, Director of Technology Strategy at Canada’s TELUS, was speaking on the same panel. He gave a matter-of-fact account of his company’s experience with SDN and NFV technologies: “We started with SDN, probably 2012, as a research project, and that has progressed to an in-market solution in Canada: we were probably the first to market in Canada, which has its pros can cons.”

Despite this, some operators are making progress. Walter Miron, Director of Technology Strategy at Canada’s TELUS, was speaking on the same panel. He gave a matter-of-fact account of his company’s experience with SDN and NFV technologies: “We started with SDN, probably 2012, as a research project, and that has progressed to an in-market solution in Canada: we were probably the first to market in Canada, which has its pros can cons.”

He explained that, “The service composition is virtual routers, virtual firewalls and devices across our network storage structure, over our own networks and partner networks, and they are all live, and probably past version two and well on the way, with all the lessons that come from that.” From an NFV perspective, Miron said that, in addition to those mentioned, TELUS has deployed infrastructure with many other virtualised functions in “two flavours”: a fully programmable deployment and individual functions that can be virtualised as necessary like “a lifecycle manager”.

He added, “Core SDN is making its way into our network, but it’s not fully fleshed-out: you have to learn to be good at software networking before you put it into the court, and make sure you’ve got robust processes and learnings across the organisation.”

Luca Pesandro, from the Standards Coordinator Technology Division of Telecom Italia, said his company has begun to deploy virtual functions in the network: “It’s a process that is going quite well and increasing day by day. We are now looking at the early stages of orchestration.” He said the company has issued a request to vendors to recommend what technology would be the best to deploy first, “bearing in mind that NFV should allow us to have multi-vendor deployments.” He also acknowledged that his company was “possibly” a little behind regarding SDN and added that it is harder to manage and it is important “to ensure that the solution is not bringing more problems instead of solving some.”

Harder than we thought

Martiny noted that although he feels ETSI has done a good job on NFV standards (which is not a universal view – see panel), “implementation has been much, much harder than we thought when we started, because it has a direct impact on each of the operators and the whole organisation, and on the knowledge of the [employees] and this kind of stuff.

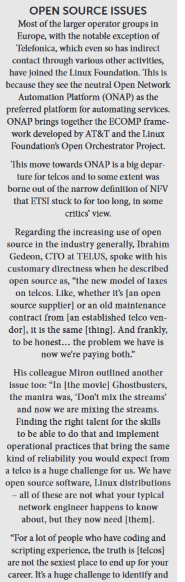

“If you are implementing NFV as it is defined in ETSI, then it has a direct impact on other business models…Now we are talking about software, not boxes, which was the original idea of NFV…and we have to play nice with the new kids on the block called open source [see panel]. It makes it all so complex to find the best approach and get the benefits of NFV.” Pesanda raised another issue: “When you have to work with other operators, you have to guarantee access on a fair, non-discriminatory basis to your devices and metro facilities that [are] virtual. That’s something you have to solve. It’s a very tricky point in your selection of what virtual functions you can deploy and in what part of the network you are able to virtualise now without unforeseen impacts on the legal side.”

More tech to fix it?

It is generally agreed that the only way to achieve the goal of end-to-end automation and zero-touch operations which will be essential in the era of 5G, is through AI. Martiny, commented, “For sure automation and AI go hand in hand, but no technology can deliver what we are looking for. The truth is that it is a combination of all those things. They are pieces of the entire future to achieve automation from end to end. That is something nobody is able to solve. ETSI is a good opportunity to push things forward.”

In particular, one issue that is exercising all operators is the gap between the reality of their customers’ experience at any given moment and what their own network-monitoring tells them is going on. As Miron remarked, “How many times have you seen an operations environment where there are 1,000 outstanding alarms? In our new world, we can’t live that way. We have to make sure we go out to the intelligence behind the alarm.” In recognition of these issues, in January 2018 ETSI launched an industry standardisation group called Experiential Networked Intelligence (ENI). So far 20 operators have joined, along with vendors and other interested parties.

Martiny explained, “We have so many different technologies, but they need to be operated jointly…and the idea of ENI is to deliver an umbrella to manage different technologies.” This will be achieved by developing an architecture and use cases, and one of ENI’s initial use cases is self-healing networks. He added, “We have a policy of talking to each other”, by which he meant the other ETSI industry standardisation groups that have a huge bearing on customers’ experience. They include: Mobile Edge Computing (MEC), NFV, Open Source Management and orchestration (OSM), and ZSM.

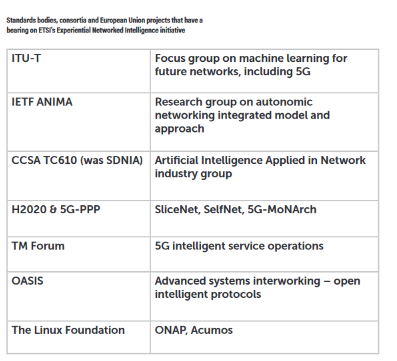

The idea is also to work closely with other bodies whose work is related (see table). Martiny noted, “Often the operational aspects come very, very late when we are defining new technologies. Nobody talks about service and network management.”

This is a trap ETSI seems to be determined to avoid this time around. Ever the realist, Pesado thinks AI systems will evolve gradually in networks and operations, “starting from a very low degree – we have none today for operations or automation – and we will build layer on layer, towards zero-touch. Building this, we need to be careful. At all levels, we are trying to achieve service and overall network management.”

Miron said he would be, “Excited to see, from an operator’s perspective, what comes outof the common service model and IETF [see table] in terms of carrier service definition, because no customer pays us for a virtualised function… To leverage [virtualisation] we need to get to defining end-to-end services so we can use the technology the way it is meant to be used. How do we get service definitions that can work across various standards bodies, as well as with vendor partners?”

ETSI’s ENI has a big task ahead.