This third decade of the 21st century looks be the last for many telcos as we’ve known them, writes Annie Turner – but that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

In March, in his company’s annual report Ericsson’s CEO and President, Börje Ekholm, wrote, “Return on capital for European operators is lower than cost of capital.” At any time this would be a gloomy outlook (although there are some reasons to be mildly cheerful – see the graphs at the end of this article), but now operators are building out 5G and, at the same time, many have, to borrow from Shakespeare, doubly redoubled their efforts to roll out fibre as fast as they can.

Their efforts are spurred on by the acute urgency of closing the digital divide in the pandemic era, which has become a more political priority for many governments and the European Commission.

Yet at the same time as highlighting the critical nature of connectivity and the network operators that provide it, some governments and regulators seized the chance to raise as much money as they could for 5G spectrum licences. Germany and Italy are perhaps the worst culprits, each raising more than €6 billion for their countries’ coffers.

This is despite many objections on the grounds it would affect the speed at which operators could afford to roll out 5G, given that many are heavily burdened by debt.

Debt and dire share prices

As well as being debt-laden, over the last decade many European telcos’ share prices have all but collapsed – in sharp contrast to those in the US, which have more than doubled. For example, in March 2011, Verizon’s market capitalisation was $108.65 billion (€91.83 billion) and now it’s $231 billion.

Telefónica group’s market capitalisation hit a high of $370 billion (€310.55 billion) in 2007 but now it stands at about €21 billion. At the end of 2015, Telefónica group’s net debt stood at more than €49 billion and is now €35 billion – not paid off from earnings but by selling assets (see below).

Last summer, BT’s market capitalisation briefly dipped to equal the hole in its pension fund – £10 billion – and, although strenuously denied, there were rumours it could be a takeover target.

True, in February Europe’s biggest operator, Deutsche Telekom (DT), announced it had broken the €100 billion net revenue barrier for the previous year, but this was largely driven by US revenues after T-Mobile merged with Sprint in April 2020 (see how the merger has also driven its brand value).

Stuck in a rut

Digitalization efforts have mostly been stuck the same ruts for a decade: in March the Technology Innovation Council published a report, commissioned by Upstream, which found 70% of respondents from operators say integration with legacy technology is the number one barrier to telcos’ digital transformation.

The same would’ve been true in 2011, although then we’d have been talking about the importance of standards and becoming Lean to achieve business and operational agility, rather than APIs, platform-based models and digital transformation.

Upstream’s CEO, Dimitris Maniatis, commented, “By working hard around the clock to keep families, friends and businesses connected while meeting unprecedented demand for connectivity, operators have seen first-hand what can be gained from digital transformation.

“By bringing their long-term plans for digitalisation forward, they can do more to help and connect communities while dramatically improving customer engagement, automation and profitability.”

Having spent billions so far on digital transformation with often not much to show for it, how will it be different now?

Different business models

One approach is operators are looking for outside investment to help them fund big infrastructure projects. Unsere Grüne Glasfaser (UGG – Our Green Fibre Optics) is a 50:50 joint venture between Telefónica Deutschland and the private equity arm of insurance company Allianz announced last October. It raised the first tranche of €1.65 billion from a syndicate of banks in March and has started deploying fibre to small communities in Germany.

Likewise Dutch operator KPN announced it would accelerate build out to rural communities by 12 months thanks to a cash injection of €1 billion over five years from a local pension company, also via a 50:50 joint venture.

BT’s CEO, Philip Jansen, who is reportedly exasperated by the lack of progress with its transformation plans, told the BBC in mid-March that, “We will keep Openreach [its wholesale access arm] in the BT family, but you know we’re very open minded about other sorts of mechanisms for making sure that we build as fast as we possibly can with all the funding that we need to do that.” Finding an investor or selling a stake are obvious possibilities.

Telefónica is seeking for an investor in its submarine cable division rather than trying to sell it for €2 billion as it originally intended. Perhaps it is suffering a bout of sellers’ remorse having sold its European tower estate for €7.7 billion earlier this year?

Selling the family silver

Other big telco groups are looking to release value from their passive infrastructure because, as Mari-Noëlle Jégo-Laveissière, Deputy CEO Europe at Orange, points out, “The value the market gives to the assets are very low: when they are within the organisational structure, they are seen as a cost. Now [as towercos] they have tremendous value.”

However, Orange has said it will keep control of its tower estate, although it might follow Vodafone’s example with its passive infrastructure unit, Vantage Towers, and sell a stake. Vantage was hoping to raise €2.8 billion in its initial public offering of a minority stake on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange at the time of writing.

Many smaller operators, though, seem content to follow Telefonica’s example, with, for instance, Iliad Group selling its tower estates to Cellnex in Poland (via Play), and Altice’s towers in France and Italy also belong to the rapidly expanding Cellnex.

Collaborating with the enemy?

Another major trend that is reshaping operational and potentially business models is the growing interdependence of telcos and the hyperscale public cloud companies such as Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud and Microsoft Azure. This will increase as time goes by, in a complex situation whereby network operators see them both as partners and powerful competitors (see our digital transformation survey results).

Certainly the public cloud companies are hyper-alert to the potential of partnering with telcos and are tripping over themselves to offer more telco-specific solutions, from Microsoft acquiring Metaswitch last year to Nokia announcing cloud RAN relationships with all three this month, and Google Cloud recently creating the Network Connectivity Center.

One scenario in the coming decade might be that the hyperscalers buy up telcos with their small change to gain ownership of arguably their most important asset – their access networks. In some countries – the Nordics, France and Germany among others – it is unimaginable that critical national infrastructure would be allowed to fall into the hands of 100% profit-driven overseas companies.

It might not be such a cultural leap for others, though. After all, in 2019 five NHS trusts transferred data processing agreements to the Google Cloud Platform after it acquired British AI firm DeepMind without consultation with patients.

Then the sale of world-leading UK chipmaker Arm to Japan’s Softbank was waved through, with some conditions regarding protection of British jobs. Now Softbank is looking to sell Arm to Nvidia, which potentially is a global problem because Arm’s business model is to license chip designs to other companies, some of which compete against Nvidia.

Regulatory priorities

Another big influence on how and how well Europe’s telcos fare over the next decade is regulation. The regulatory regime in Europe has been much criticised for a range of things, from extortionate spectrum auctions, as mentioned, to the European Commission being more interested in fighting for consumers’ rights and lowering prices than ensuring operators have sufficient profits to reinvest in infrastructure that is critical to the social and economic wellbeing of the entire continent.

Ericsson’s Ekholm wrote in his annual report, “We believe that Europe needs to review its regulation of operators [and] spectrum policies, while also allowing for industry consolidation.”

“In Europe we have about 300 network players, in the US they have about 30,” Javier Torre de Silva, Global Telecoms Lead at law firm CMS, points out. This means that even in small European markets there might be four competing networks trying to scrape a living. In a number of cases, the European Commission has prevented consolidation, such as the proposed 2016 merger between Three and O2 in the UK (last year this was overruled by the European Court and the thinking behind it discredited).

Further, as Torre de Silva points out, to get permission for base station sites can take literally years. He says, “It seems a regulated market, but it is a highly fragmented market,” adding, “You cannot expect the private sector to invest more than €1 trillion, which it is going to cost [to deploy 5G], if you don’t provide them with the opportunity [to earn it back].

“The returns should be foreseeable and safe from regulatory gaps. In practice, because the regulatory [situation] cannot be foreseen in the long term, [operators] cannot make good investment decisions. And if you [go ahead], you add a little bit on the return because of that regulatory risk.

“If the regulation were safer, more predictable, and lighter, this additional return required to offset regulatory risk would be reduced… but the authorities probably don’t see that they are part of the problem.” It will be interesting to see if the pandemic and the resultant rescue plan (see below) reflect a change in the Commission’s approach.

Looking to government

Already there are more private that public networks in existence, and Rethink RAN Research predicts 1.56 million private 5G cells deployed by 2027. Although enterprise is the great hope for operators regarding new revenue streams to replace those that are drying up, these networks may or may not involve operators and in many that do, operators will just be providing the connectivity.

The bonanza promised from new 5G services for enterprises may or may not materialise, but in the meantime public cloud companies are making swift inroads into telecoms.

Having proved their worth during the pandemic, operators are hoping governments at national and European Union level will step into the investment breach. For instance, Orange, Telefónica and Vodafone opcos in Spain are reportedly jointly applying to the country’s Ministry of Economic Affairs to undertake large infrastructure projects, funded by the EC’s €1.8 trillion pandemic recovery plan.

In mid-March, as the European Council met to discuss the future of Europe’s industrial and digital policy, ETNO published a report claiming that €300 billion in telecoms network investment would create 2.4 million new jobs, but investment must also go into stimulating digital demand and providing people with digital skills.

In January, Europe’s big four operator groups – Deutsche Telekom, Orange, Telefonica and Vodafone – expressed their support for Open RAN and highlighted the need for government support for it with funding and policies to reach its potential. Many countries are looking for government subsidies to roll out fibre to the most difficult-to-reach, commercially unviable areas.

The banks were famously said to be too big to be allowed to fail in the global financial crash of 2008. Europe’s telcos aren’t in such a dire position yet, but they are banking on being too critical for governments to deprive of funds. Who could have foreseen this back in the heady days of privatisation and liberalisation, and the mobile boom?

Good news for Europe’s telcos

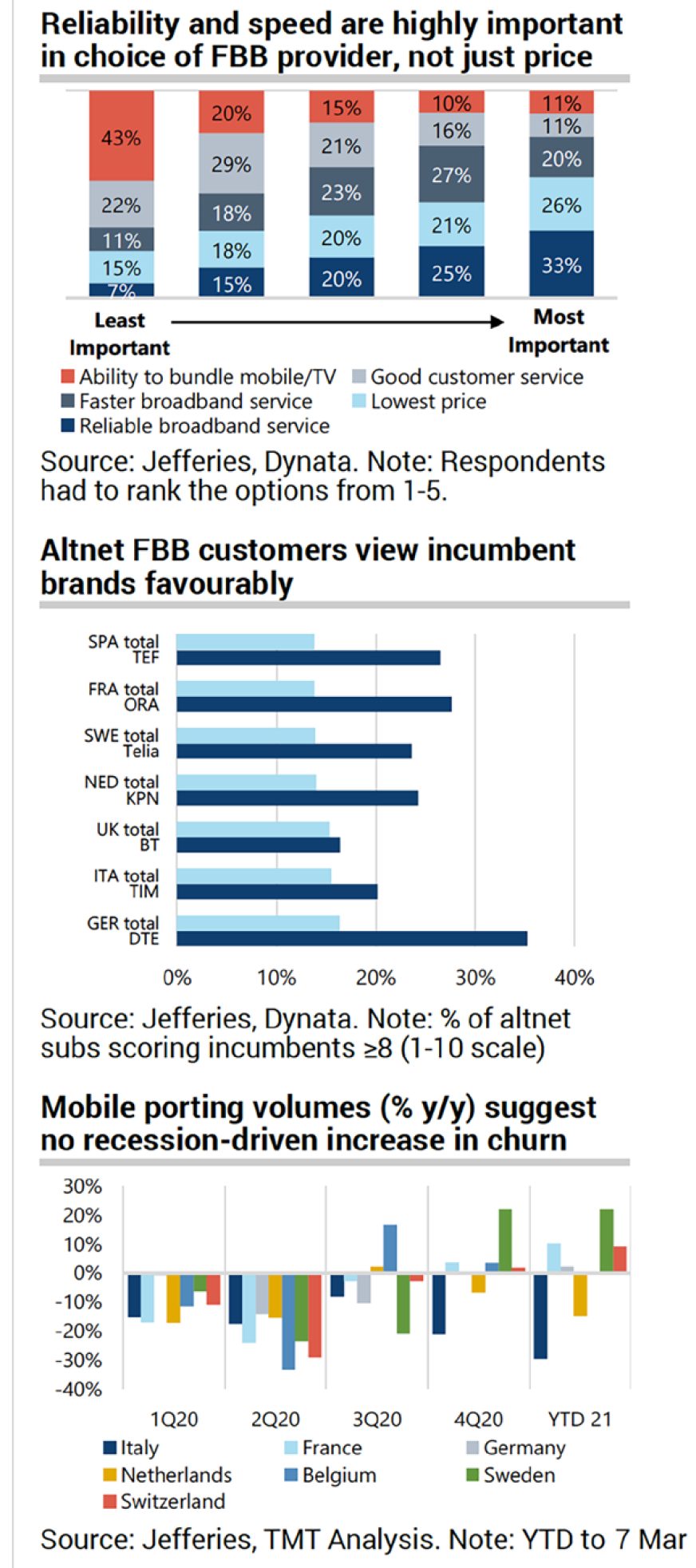

Jefferies Equity Research Europe Telecoms reckons that, “Several large cap telcos will return to growth in 2021, as pandemic headwinds unwind.” It also found that there has been no increase in churn during the pandemic, despite pressure on household income. It predicts that with connectivity consumers will be more interested in quality than price and will tend to look favourably on incumbent brands.

This article originally appeared in the Q1 edition of Mobile Europe & European Communications which you can download from here free of charge.