The World Radio Conference 2023 (WRC-23) concluded in December and was attended by more than 3,900 delegates from 163 countries

The World Radio Conference 2023 (WRC-23) is held every four years under the auspices of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), itself part of the United Nations. The most recent took place in at the Dubai World Trade Centre in Dubai and concluded in December.

The WRC-23 is a treaty conference, meaning it can change international regulations on the use of radio spectrum for different services, including mobile, which in ITU parlance is International Mobile Technologies (IMT). All kinds of service providers and technology companies look to its outcomes for certainty in investment and planning, although the decisions made here are just the start of the process.

Regional and in-country regulations must be put in place before the spectrum finally becomes available for services, mindful of factors like their own and neighbours’ existing usage rights.

6GHz complications

Perhaps one of the most eagerly awaited outcomes of the WRC-2023 concerned the use of 6GHz spectrum for 5G and 6G. Spectrum for 6G will be an even hotter agenda item at WRC-27 as the expected but unspecified deployment time of after 2030 grows closer. With this in mind, WRC-23 also approved the study of the bands 4400–4800 MHz, 7125–8500 MHz and 14.8–15.35GHz for IMT.

The outcome regarding the use of 6GHz for 5G in the shorter term was celebrated by the mobile industry. The GSMA said in a statement as the conference concluded, “

“The WRC-23 decision to harmonize the 6GHz band … is a pivotal milestone, bringing a population of billions of people into a harmonized 6GHz mobile footprint. It also serves as a critical developmental trigger for manufacturers of the 6GHz equipment ecosystem.”

In fact, the situation is not clear cut. For one thing, the ITU’s IMT identification (ITU-speak for allocated to) for the Upper 6GHz band in all regions is limited to just 100MHz, between 7025-7125MHz.

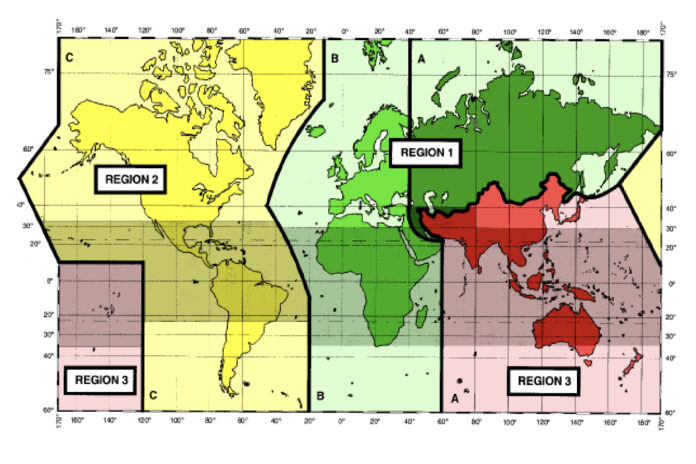

Consequently, it is not accurate to say, as some commentators have, that the entire Upper 6GHz band was identified across all regions for mobile (graphic above supplied by the ITU, showing the radio regions). In Regions 2 and 3 (see map), only Brazil, Mexico and Laos, the Maldives and Cambodia, were identified for the 6425 to 7025MHz section.

There appears to be growing support for IMT in the 6GHz band by other countries but some were prevented from joining the IMT identification by concerns from neighbouring countries. Mobile supporters hope this will shift at WRC-27 as a result of more study.

For now, countries’ and regions’ policies regarding the use of 6GHz vary, for instance:

• the US has made the entire 6GHz band unlicensed and available for Wi-Fi

• China has opted to use it for 5G and 6G

• India remains undecided

• Europe will study the viability of Wi-Fi and IMT sharing the spectrum during 2024 and 2025, with a final decision expected in 2026.

Nevertheless, as Eiman Mohyeldin, Global Head of Spectrum Standardisation at Nokia, explains, “The upper 6GHz is for 5G Advanced technologies and Europe, the Middle East and Africa has 700MHz allocated to this.

“We welcome and are very thrilled by this outcome because it will be additional resource allowing us to add new applications and features…operators can extend their resources and offer all those things we dreamed about [when 5G was mooted]. It’s all about how can we get data in a very speedy way.”

Even the Wi-Fi Alliance, which had lobbied for 6GHz to be given over for unlicensed use by Wi-Fi, was chipper, presumably as potentially sharing the bandwidth in Europe is better than no bandwidth in the upper register of 6GHz at all.

The low(er) down

There were more moves to harmonise the use ofultra-high frequency (UHF) spectrum in the 470-694MHz band.Lower frequencies are helpful for wider area coverage in rural areas rather than for boosting capacity. There was a secondary ruling regarding its identification for mobile in Europe (Region 1).

Mohyeldin explains that the secondary ruling means that Europe can deploy IMT once the decisions on the future use of the UHF band are made within the continent. The planned review of the TV broadcast’s use of the band should conclude in 2025. In the meantime, Italy and Spain are still using it for broadcast.

There are also issues about using the band close to the Russian border and the border with Belarus, as it is used for other purposes there and could cause or suffer interference. Hence the spectrum can be used for mobile, but the bandwidth is not ‘protected’ for mobile’s exclusive use.

Eleven countries in the Middle East were allocated 614-694MHz for mobile on a primary basis. This means there are strict conditions attached to its use and careful coordination is needed for use close to the border with Iran.

Some African countries like Nigeria, Namibia, Senegal, Ghana and Somalia, also wanted primary allocation of the 600MHz frequency, but it was not possible to coordinate this due to neighbouring countries’ issues. There will be further discussion of this for African countries at WRC-31.

Satellite generations collide over spectrum

The was some manoeuvring among operators of the new low earth orbit satellite systems (LEOs) and the owners of older constellations operating in higher orbits.

These new kids on the block and other LEO operators want a relaxation of the Equivalent Power Flux Density (EPFD) limits that dictate how much power LEO operators can use to transmit signals to prevent interference with those higher orbit, such as those of fixed satellite operators ViaSat and SES.

The LEO constellation operators complain that the regulation is outdated and that modern tech means that being allowed to use more power would generate more capacity for customers without affecting the geostationary orbit operators.

Diverse but united opposition

Not everyone is convinced and interference with the GEOs is not the opposition’s only concern. The proposal was opposed by Brazil, Indonesia, Japan and others. They are concerned about the dominance of newer mega-constellations – the ethereal equivalent of hyperscalers – in terms of potential spectrum-grab and undermining the huge investment sunk into the older ones.

As Peggy Hollinger wrote in the Financial Times, whether parties were objecting on competitive, sustainability or security grounds, they formed a formidable opposition. Proposals to review the rules at the WRC-2027 were denied but permission was granted for technical studies of how power limits could be changed to proceed. If they are successful, it would hard to see how rule changes could be denied.

In that case there would be genuine reasons for concern that operators from the world’s most wealthy companies (and countries) would focus on profit rather than the common good. And the alarming potential of allowing a handful of billionaires to control constellations was demonstrated in 2022, such as to intervene in wars.

Musk allegedly caused Starlink satellites to be turned off during a submarine drone attack by Ukraine on Russian warships in 2022, causing the offensive to fail. Musk reportedly opposed inflicting a “strategic defeat” on the Kremlin.

According to the biography of Musk published in 2023, written by Walter Isaacson, Musk asked the author, “How am I in this war?” in an interview. “Starlink was not meant to be involved in wars. It was so people can watch Netflix and chill and get online for school and do good peaceful things, not drone strikes.”

Satellite-to-smartphone

Meanwhile, WRC-23 sanctioned studies to progress work on satellite services variously described as direct-to device, direct-to-cell or direct-to-mobile. In other words, enabling a standard smartphone to communicate via satellite. Mohyeldin says, “This is a crucial thing. You can see that countries are going to study it, but the potential allocation is going to be different from one region to another.”

Elon Musk’s SpaceX successfully launched six Starlink direct-to-cell (mobile) satellites in January, having already launched about 5,000 satellites in four years. Amazon founder, Jeff Bezos, has only two LEOs in orbit for his Project Kuiper, but has large number of launch dates booked from this year and is racing to become operational.

Meanwhile, the market is becoming ever more crowded. China is to launch two megaconstellations and Iridium Communications announced Project Stardust which it describes as “the evolution of its direct-to-device (D2D) strategy with 3GPP 5G standards-based Narrowband-Internet of Things (NB-IoT) Non-Terrestrial Network (NB-NTN) service development”.